Dealing with the products of combustion: Part 1

August 26, 2019 | By Rob Waters

Contractors who install gas-fired condensing boilers know that dealing with the products of combustion is a big challenge when installing these appliances. Flue gases exiting the appliance are laden with moisture, and liquid condensing from the combustion chamber and vent pipe is acidic and corrosive.

Dealing with this low temperature flue gas and liquid condensate must be done properly to avoid damages to the building and the appliance, costly call backs and angry customers. This is especially true when retrofitting new modern condensing appliances into old buildings, where contractors face challenging building and lot restrictions, and difficulty accessing drainage.

Part 1 of this article will look at the issues and solutions for dealing with venting of flue gas from condensing appliances. Part 2 in HPAC October will look at disposing of liquid condensate.

Condensing furnaces, water heaters and boilers have been gaining market share steadily over the last 15 years. Recent changes to the federal energy efficiency standards mean that the push to condensing products is going to get even stronger. NRCan Amendment 15 was published in the Canada Gazette, Part II on June 3, 2019 and introduces higher minimum efficiency regulations for a wide range of HVAC products.

Condensing level regulations have been introduced for gas boilers and certain sizes and types of gas water heaters. For gas-fired boilers, all products must be condensing (>90 per cent) by 2023 for residential (<300 MBH), and 2025 for commercial (>300 MBH). Gas-fired instantaneous water heaters are also all going to condensing levels in 2020.

Approximately 75 per cent of the new residential gas boilers currently sold in Canada are already at or above this efficiency level so the issues of dealing with flue gas and condensate are not new to the industry. However, now with these new regulations in place, all installations must go with condensing boilers and contractors will no longer have the option to install non-condensing. Many existing buildings that currently use non-condensing boilers will have to be upgraded to condensing boilers when it is time for replacement of the old unit. In some cases, this will result in very challenging retrofits.

Over the last 15 years many lessons have been learned related to dealing with the products of combustion from condensing appliances. Venting products and techniques have been introduced to provide solutions for new heating technology. Consultations with many experts in the venting field has shown me this is an area where the good, the bad and the ugly certainly applies. Currently industry veterans that have been at it for many years see many issues going on now with installations.

The most common venting materials used for condensing boilers are PVC and CPVC pipe, polypropylene pipe and stainless steel with the latter two materials both available in rigid and flexible pipes. All of these products have different temperature ratings, and long-term safety must be considered when choosing.

What happens if the boiler set point temperature is turned up to the maximum, or the boiler heat exchanger scales up over time? Both of these conditions can cause the flue gas temperature to go higher than what would normally be expected. Will the vent material safely stand up to these conditions? Vent pipe operating above its rated temperature may become compromised over time and create unsafe situations.

All of these venting materials have pros and cons and it is usually up to the individual contractor to choose which product they prefer and which is best suited for the application. The installer must consult the appliance manufacturer’s installation manual to check what venting is approved for the specific appliance. For commercial buildings, the combustible (plastic) vent piping must meet all Part 3 requirements of the Ontario or National Building Code, especially related to Flame/Smoke Ratings and firestop requirements. Installation problems can occur with any material if the manufacturer’s installation guidelines are not followed properly.

Contractors must carefully follow all the guidelines related to making fitting connections, pipe support requirements, wall and roof penetrations and terminations, etc. The reality in some projects is that sometimes not a lot of thought is put into the choice of vent product. Whatever is the cheapest, whatever is readily available at the distributor and whatever is fastest and easiest in terms of installation are sometimes determining factors. This does not always lead to the best long-term results for the customer.

PVC vent pipe is generally the most commonly used product due to its lower cost and wide availability, however it is only rated up to 65C/149F and can only be used for certain appliances. CPVC is rated up to 90C/194F which makes it suitable for a wider range of products, but it carries a higher price tag.

PVC/CPVC pipe and fittings are very rugged Schedule 40 thickness and provide excellent beam strength, durability and resistance to puncture. PVC/CPVC both rely on solvent welded joints which provides a very permanent and reliable connection.

Problems can occur when care is not taken with the installation, especially if the wrong solvent is used or if the solvent welding procedure is not followed. Joints cannot be taken apart once welded, and in cold weather, joints must be primed prior to gluing below 0C.

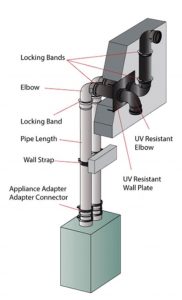

Polypropylene venting material is rated up to 110C/230F and is gaining favour with some due to its higher temperature rating, ease of use, lighter weight, versatility and fast installation time. The connection joints use a gasketed male-female connection that require the use of a locking band after the fitting has been installed.

Problems can occur if the bands are not used or installed improperly. If the pipe is sloped incorrectly then it is possible for the joints to leak. One industry veteran told me he no longer uses CPVC as the gluing of joints can be messy and he likes polypropylene as it is fast and easy to work with and uses simple non-glued joints. Stainless steel venting offers the highest temperature rating of up to 249C/480F, and also uses a gasket connection on rigid pipe. Flexible pipe for relining chimneys is available in both polypropylene and stainless steel, with stainless steel being the most popular.

Care must be taken when cutting any plastic pipe to length. The pipe end must be cut as square as possible to provide the best seal with the fitting. A wheel cutter is recommended for use on CPVC rigid pipe, but these cutters do create a raised edge on the pipe end, which must be removed with a reamer.

If a blade or chop saw is used on any pipe, the pipe end must be completely de-burred inside and out, and the end may need to be bevelled on the outside. Failure to do this can create problems with a glued fitting or damage the gasket on a polypropylene fitting.

Side wall venting has become the most common method of venting condensing appliances, to the point where everyone just thinks “that’s the only way it’s done now right?”

The reality is that this is the area where most venting problems and issues occur. Flue gas exiting at the side of the building close to the ground comes in contact with walls, windows, driveways, swirling winds, plants and sometimes people. This can create issues with large visible plumes of moist flue gas, damage to the façade, angry neighbours, dead plants, ice formations and flue gas recirculation.

The issue is exacerbated by how little space is between houses in new subdivisions, and the fact architects love open plans and make no allowances for vertical venting. The issue has become severe enough that municipalities in Alberta and BC are starting to put restrictions on side wall venting of appliances. Minimum distances have been increased and redirecting of the vent plume must be addressed.

One of the most serious side wall venting issues in relation to the appliance itself is flue gas recirculation. This is where flue gases are drawn back into the combustion air inlet pipe then re-enter the appliance. Flue gas recirculation is usually caused by problems with the location of the vent terminal. Swirling wind can whirlpool flue gas, causing it to have a tumbling effect and hang close to the ground.

It is important to recognize and avoid vent terminations that are too close together, located in building corners or with unusual wind patterns. Recirculated flue gas can be very damaging to the appliance and can eat away components such as the inlet venturi and radial fan bearings.

Recirculation often results in very poor combustion, high CO levels and unsafe conditions. Intermittent burner lock-outs will often result due to this recirculation and they can be hard to diagnose. By the time the technician gets in to service the appliance, the wind may have dropped and the appliance can be running fine again.

Frost and ice formation is the other major issue with side wall venting. Ice and frost can form on the walls, windows and landscaping near the vent terminal. When the vent terminates in the space between two buildings ice and frost can form on the walls and windows of the adjacent buildings. Ice that builds up on driveways and sidewalks creates very unsafe conditions. These ice and frost issues are often very contentious issues with neighbours.

Icing issues can be made much worse when the venting is sloped incorrectly. Venting should always be sloped continuously back towards the appliance so it can be easily drained away inside the building. When the slope is in the wrong direction, condensate will run towards the outside of the building and drip out the vent pipe. This will result in large formations of ice at the terminal, and it is not uncommon to see huge icicles forming all the way to the ground.

Although not as common, frost can also build up on first 6 in. of the inlet air pipe of the appliance. This can sometimes build up to the point of a burner lock-out.

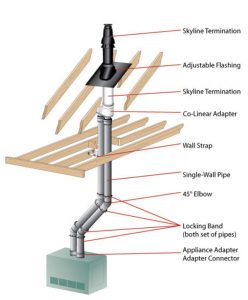

All the venting professionals I consulted advocate for vertical venting as being the best option for almost any situation. Vertical venting may not be the cheapest or easiest solution, but it can successfully make all of the problems listed earlier disappear. When flue gas is terminated up above the roof line, flue gas is dispersed into the atmosphere well above the level of people, plants and buildings.

Two pipe and concentric pipe options are available for vertical venting. Some contractors will use a hybrid approach with the vent exhaust pipe going vertical and the inlet air pipe coming horizontally from the side of the building.

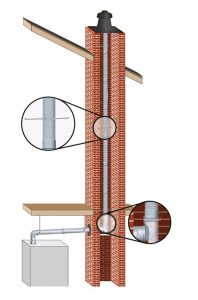

When retrofitting an older building with an existing chimney, flexible liners of polypropylene or stainless steel offer a reliable vertical venting solution. Flex venting can be run up existing masonry or B-vent chimneys. However according to one vent supplier, many contractors are not aware, or do not often consider this method as a venting option.

A service contractor in Toronto I spoke with says he sees too many instances where contractors don’t think about the neighbours when venting. He loves flexible chimney liners and refers to them as a “peacekeeper,” as it avoids any issues with sidewall venting and dealing with neighbours in tight retrofits.

I have heard many side wall venting horror stories involving driveways covered in ice, seven-foot long icicles, stucco and masonry walls severely damaged by water egress and freeze-thaw cycles, trees killed, appliances locking out and internally damaged, and neighbours almost coming to blows. After listening to these tales of venting woes,

I believe that it is prudent for contractors to take a long hard look at the unique logistics of each job and inform their customers of their venting options, both horizontal and vertical. Most customers are not aware of the issues of sidewall venting, and are relying on the contractor to guide them to the best option for their building.

Dealing with the products of combustion from high efficiency equipment must be re-evaluated by everyone involved in the mechanical world. Architects and engineers must reconsider side wall venting and avoid open plans with no allowance for vertical venting.

Contractors often do not look closely enough at the project’s unique venting requirements and get caught underpricing the job. This is what leads to the quick, inexpensive venting job, and can end up leaving the building owners stuck with hefty façade or equipment repairs, angry neighbours, unsafe ice buildup, and unsightly flue gas plumes, and equipment lock-outs. We should all strive to make sure these things do not happen. <>

Robert Waters is president of Solar Water Services Inc., which provides training, education and support services to the hydronic industry. He has over 30 years experience in hydronic and solar water heating. He can be reached at solwatservices@gmail.com.

ROB WILL BE ADDRESSING THIS CHALLENGING ISSUE AT MODERN HYDRONICS SUMMIT 2019.