Radon, Canadianized

November 6, 2018 | By Jillian Morgan

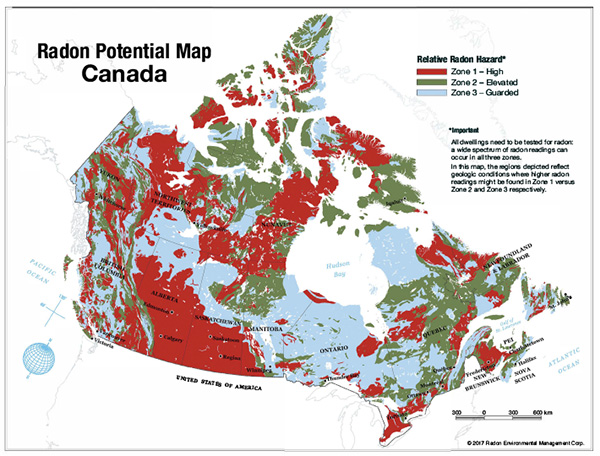

Map courtesy Radon Environmental Management Corp.

As uranium begins its cyclical decay chain in Canadian soil, homes on the surface act like a suction cup and draw in its deadly by-product: radon.

Odourless, colourless and tasteless, radon gas is just one domino in a radioactive cascade that enters structures new and old across the country, contributing to more than 3,300 lung cancer deaths per year.

“It’s the worst thing no one’s ever heard of,” said Anne-Marie Nicol, associate professor at Simon Fraser University’s Faculty of Health Sciences in Burnaby, BC.

As a public health researcher, much of Nicol’s work focuses on environmental carcinogens, specifically radon–the second leading cause of lung cancer in Canada.

“We’ve kind of shrugged this off as a smoker’s condition, but if fewer people are smoking we’re realizing there are other things that cause lung cancer as well,” said Nicol.

The latest technologies in radon remediation and mitigation offer a means to end the reign of this silent killer in homes and buildings, as long as the HVAC contractors behind those structures stay in the know.

HEALTH RISKS

Canada is the world’s second largest producer of uranium–its soil so rich in the metal that there is always a measureable amount of radon in the air.

Outside, it dissipates and mixes with other gases, so concentrations drop to relatively harmless levels, ranging from 10 Becquerels–a measurement of radioactivity–per cubic metre (Bq/m³) to 30.

Inside, however, those levels can vary drastically from one structure to another.

Radon exists, on average, three to four days in an indoor environment before it decays, at which point it gives off radioactive alpha particles in addition to progeny, or “radon daughters.” The metal progeny “stick” to the sensitive lining of the lungs, further decaying and emitting radiation.

“People call radon radioactive, but it’s actually the decaying process that causes the problem,” Nicol said.

In 2007, Health Canada reduced its guideline for radon in indoor air from 800 Bq/m³ to 200. Comparably, the World Health

Organization recommends a 100 Bq/m³ baseline, and the U.S. standard sits at 150.

“I’d like to see the action level dropped,” said David Innes, sales director at Radon Environmental Management Corp.

Headquartered in Vancouver, BC, Radon Environmental–an environmental and building science company–published the first geology-based radon map of Canada in 2011.

“There was some level of radon awareness in Canada the late 1970s and early 1980s, and it seemed through a government change it just fizzled away. I don’t really have an explanation of why that’s the case but I can say the U.S. is, in my opinion, about 30 years ahead of Canada in terms of radon awareness.”

In 2017, the company partnered with Airwell Technologies to tackle the emerging threat of radon in water, namely from private wells. The jointly released product “off-gasses” radon-contaminated water before it enters a home.

“Dissolved radon can be released into the indoor air through agitation from household use, so showering, dishwashing, etcetera, but generally the contribution of dissolved radon from ground water is a small percentage of the overall airborne radon found in most homes,” said Kelley Bush, manager of radon education and awareness at Health Canada.

Still, there’s a hypothesis that drinking radon-contaminated water could “impact different parts of the stomach and gastrointestinal system, and possibly bladder,” Nicol said.

“A lot of the things that are done to reduce radon in homes and buildings are the result of how our buildings are built and designed or renovated,” she added. “Raising awareness in [trades] people that what they’re doing is contributing to cancer prevention is really important.”

SOLUTIONS

In 2014, Health Canada and the non-profit Canadian Association of Radon Scientists and Technologists formed the Canadian National Radon Proficiency Program (C-NRPP).

C-NRPP offers courses in radon mitigation for accredited contractors, including how to install passive systems and active systems–the latter, more generally used strategy known as active soil depressurization (ASD).

ASD involves connecting a pipe, or “radon stack,” to the foundation floor slab of a home, while an attached radon fan continuously discharges soil gas to the outdoors via the stack’s exit. In the U.S., that stack typically passes through a living space and discharges above the roofline, with the fan located in an uninhabited area, such as an attic. But for America’s northern neighbour, this configuration presents challenges.

- A typical ASD system PHOTO Rob Mahoney/Radon Works

According to monitoring by the National Research Council, soil gas inside the stack sits between 80 and 100 per cent humidity. When temperatures dip well below zero for extended periods of time, ice or snow blockage at the system’s exit is more likely. For this reason, ASD systems in Canadian homes typically exit at the sidewall near ground level, with the fan located in a basement.

“Those strategies are not new, they’re actually very commonly used but we didn’t quite understand their performance and impact in Canada,” said Liang Grace Zhou, senior research officer with NRC’s Intelligent Building Operations Unit and lead for all radon control research projects.

Despite its effectiveness, the Canadianized ASD system can lead to other problems, such as radon fan leakage into habituated areas, introduction of unwanted air and the dispersion of high radon concentrations just above the grade.

In a search for alternatives, NRC has undertaken studies on passive systems, which do not use a fan and instead naturally draw soil gas through the pipe and discharge it outdoors above the roofline via the stack effect.

Between September 2017 and March 2018, the organization conducted a test on this system in four Ottawa homes. It monitored indoor radon concentration, as well as airflow, air speed, temperature, RH and pressure within the stack, in addition to pressure from the sub-slab area.

Within the first year, radon levels dropped 40 to 90 per cent.

“This is a solution for Canada,” Zhou said. NRC plans to conduct another field study on passive systems this year in B.C., since the province’s building codes require homes in high-exposure zones to install a full passive stack.

With a push to net zero energy readiness by 2030, NRC has also developed a semi-detached zero energy ready house in Ottawa, which will be used to study alternative radon control systems.

In other building types, such those with a larger footprint, ventilation can alleviate high radon levels, though this requires a slightly different protocol, Zhou said.

“In the commercial environment, there are many forms of HVAC equipment that in some cases can be manipulated to abate the radon entry,” said Rob Mahoney, owner of Radon Works, an Ottawa-based radon control company.

“Bottom line, there is no such thing as zero radon, any standard structure will have a measureable amount.”

ACTION

“In Ontario, we have Tarion Warranty, which guarantees a home to be less than 200 Bq/m³, but unless the occupant tests it goes unnoticed, just like the crack in the foundation behind the finished wall,” Mahoney said.

Despite a slew of C-NRPP approved radon monitoring devices, few homeowners test, so data on radon concentrations in homes and buildings is unstable. Other challenges are presented too, with the rise of green structures that are virtually airtight, meaning newer homes typically have higher levels of radon.

“As codes change, due to product innovations and energy costs and sometimes even common sense… We solve one problem but create another,” Mahoney said.

Each November, the Take Action on Radon network, led by the Lung Association and Scout Environmental with support from Health Canada, hosts Radon Action Month. The campaign aims to raise awareness about the dangers of radon and encourage homeowners to test. This is especially timely as levels can rise in the winter months when homes are sealed up.

Health Canada is also in the early stages of an epidemiological study to find indicators that the body is responding to what it terms, “chronic, low-dose exposures,” Bush said.

“Radon is a very challenging health risk issue to get people to pay attention to,” she added.

“You can’t see it, you can’t smell it, you can’t taste it, so you don’t really believe it’s there… It doesn’t get you angry or worked up because its naturally occurring, its everywhere in the ground, its in every single home and building, so its challenging.” <>